“I think that the anti-theory shift is linked to the vicissitudes of the ideological context. After the offi cial end of the Cold War, the political movements of the second half of the twentieth century have been discarded and their theoretical efforts dismissed as failed historical experiments. The ‘new’ ideology of the free market economy has steamrolled all oppositions, in spite of massive protest from many sectors of society, imposing anti-intellectualism as a salient feature of our times. This is especially hard on the Humanities because it penalizes subtlety of analysis by paying undue allegiance to ‘common sense’ – the tyranny of doxa – and to economic profi t – the banality of self-interest. In this context, ‘theory’ has lost status and is often dismissed as a form of fantasy or narcissistic self-indulgence. Consequently, a shallow version of neo-empiricism – which is often nothing more than data-mining – has become the methodological norm in Humanities research.”

Rat Bastard Protective Association

“Conner also endorsed works anonymously with the Rat Bastard stamp. Villa recalled other ways in which Conner used the stamp: “He would look at signs on telephone poles and [say,] ‘God, that’s a great advertisement.’ Clunk. Even the waitress with her new black, blue, white leotards got stamped right on the ass. Rat Bastard. He’d stamp tables, menus, it was just this fantastic piece that he was doing all the way through.” Irreverent, wily and audacious, Conner reflected the tradition of San Francisco artists who embraced their role as heirs to the Dada legacy. Now he threatened to go further by abandoning authorship altogether, and he wanted to take his friends with him.”

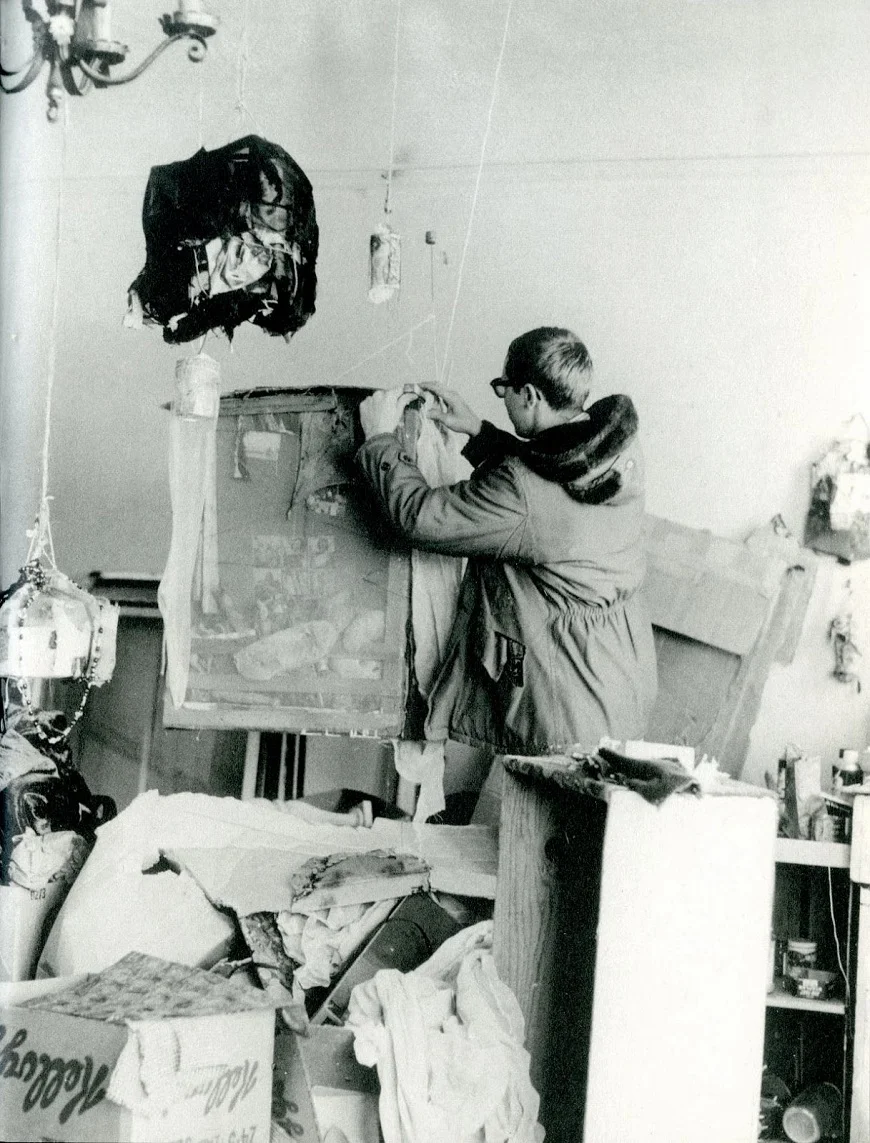

Painterland, in 1965.

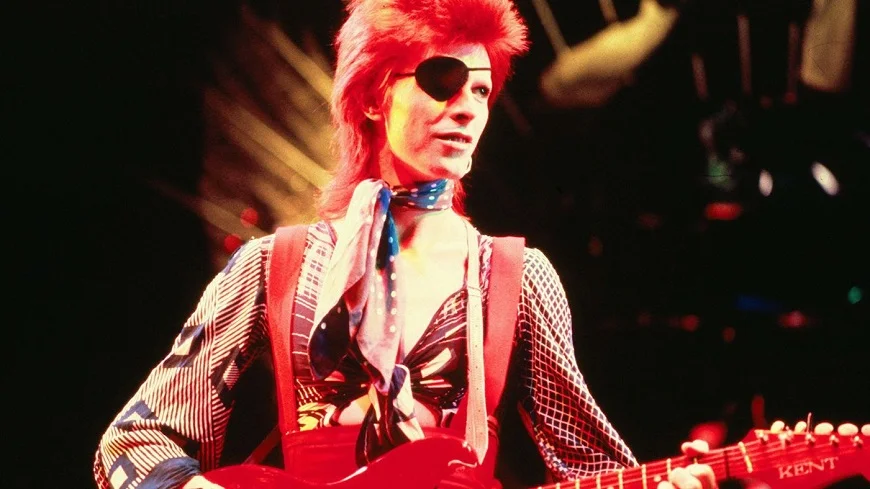

art school

“Because Bowie’s most important lesson was how to be an artist. It’s become a truism that he influenced generations of art-school students and it’s because he was art school for so many.”

stills

Pharmakon

“Color is also a luxury item sold like controlled substances by the ounce or gram. The Greeks don’t call color pharmakon for nothing. The word means color, drug, poison, remedy, talisman, cosmetic, and intoxicant. Art stores supply all of these at once; the ultimate bohemian experience. As the poet Lisa Robertson wrote: “Color, like a hormone, acts across, embarrasses, seduces. It stimulates the juicy interval in which emotion and sentiment twist.” And indeed, the purchase of color is an entirely capricious experience — an art store is a kind of fetish shop offering chromatic luxury in aisles, like a supermarket but with an air of esoteric connoisseurship. A good metropolitan art store is usually an intimidating multistory affair staffed by sullen but knowing art school clerks, with staircases to mysterious and all-encompassing storage rooms. It is set up like a bazaar where shoppers can touch and feel everything before buying, although at Madison Avenue prices. The more you touch it, the more you want it. That new gold lacquer, that little jar of iridescent lilac, that special kind of creamy modeling paste. When was the last time I got past the checkout with a big basket of oil paint for less than a thousand? But I shell it out because I need this equipment and am seduced by the ritual of purchasing it.”

sem título, 2012.

Július Koller

o jogo das tribos do não

Talvez a maior resposta que o homem ocidental tenha oferecido à corrida industrial do final do século XIX, que adentrou todo o século XX e que, hoje, permanece ressoando sob expressões como "internet das coisas", "design thinking" ou "big data", seja o retorno apaixonado ao mundo de regras paralelas do jogo. Praticamente toda poética de resistência que tentou ganhar terreno no século passado foi um convite à "brincadeira". Mesmo quando ela foi séria. E, aqui, me lembro do hipotético compartilhamento etimológico das palavras brincar e vincular. O jogo prende quem joga.

Hoje são bem famosos os figurinos de Oskar Schlemmer para as festas da Bauhaus, nos anos 1920. Sempre que vejo essas fotos, encontro algum paradoxo com o projeto de um design belo e funcional (a função antes da forma), mas nunca fui ler mais detalhadamente a respeito, para entender a justificativa para a "montação" delirante. Que tipo de indústria assumiria o risco de introduzir essas fantasias, em larga escala, na vida cotidiana?

A estética do jogo atravessou as vanguardas e toda iniciativa contracultural que tentou propor alternativas à vida de produção e consumo. Mesmo uma Bauhaus, que buscava racionalizar a criatividade, teve momentos de sedução diante da imaginação não utilitária. À sua maneira, marcas como Google (e toda geração Vale do Silício) forjam isso quando circulam a decoração divertida dos seus escritórios na Suíça (berço dadá!).

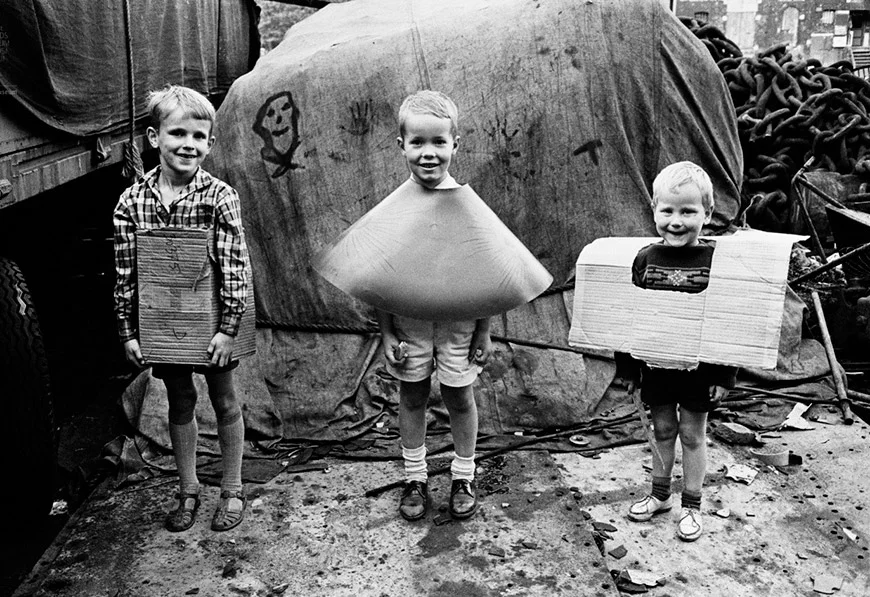

Coincidência ou não, olhando algumas fotos do Ed van der Elsken, fotógrafo holandês que, a partir da década de 1950, entre Amsterdã e Paris, sempre flagrou o jogo das tribos do não, achei essa imagem beleza de 1961. Fiquei um tempo imaginando como esse retorno à brincadeira é mesmo o resgate do ritual "primitivo" perdido, que tanta possibilidade de mundo abria ao ser que pensa por meio das imagens. Fiquei pensando o que de errado aconteceu, no meio do caminho, que trocou a vida do "pode ser" pela realidade do "não pode", o cotidiano de imaginação pela publicidade da sugestão. Turner, o antropólogo inglês, põe a culpa na industrialização da cultura, que separou o trabalho do lazer.

se vende

A organização do (eco)sistema das artes, as lógicas de produção e circulação da obra, na contemporaneidade, são questões recorrentes diante da discussão das fronteiras entre arte e entretenimento, arte e publicidade.

É sempre curioso observar ecos da estética de tradição idealista nas posições de defesa da autonomia do objeto artístico. Por outro lado: como, se é que é necessário, separar artistas e operadores do mercado, criadores livres e reprodutores orientados pelo consumo? Faz sentido admitir que são subjetividades que se guiam pelo "grau" de resistência que oferecem às engrenagens do capital transnacional gato miau?

Esses debates vão e voltam, dão voltas ao redor do próprio rabo, e dificilmente terminam em interpretações definitivas. Seja como for, foi nisso tudo que pensei quando li essa reportagem sobre a aquisição de trabalhos do OPAVIVARÁ pelo Guggenheim.

the stillness of the violin

Um dos mais bonitos temas do ano, um dos discos 5 joias de 2016.

Walter Benjamin es el coleccionista nómada que no para de adquirir y que lo va perdiendo todo

“Gracias al testimonio de una compañera de huida sabemos cuál fue el último objeto de valor que conservaba Walter Benjamin: un reloj antiguo, de oro, un resto arqueológico de vida burguesa, un recuerdo de familia.”

blog

2017 vai assistir ao retorno dos blogs. Por um lado, parece ser a derrota das redes sociais, do diálogo, das aproximações, do grupo. Só parece: vimos que FB e cia. derrubaram a abertura à diferença.

Nessa expectativa, passarei a postar, por aqui, o que, durante alguns anos, compartilhei na timeline. Que seja para poucos, mas que seja por mais.

seres modernos

ser moderno

queremos ser contemporâneos

queremos qualquer

ser-se

se/quer

seremos